Crohn's disease

Highlights

Crohn’s Disease

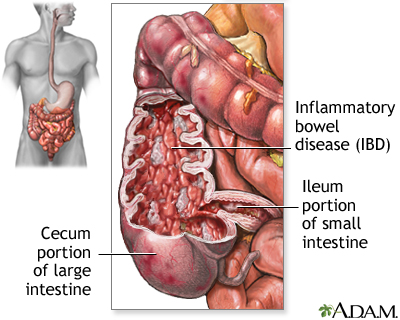

Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis are inflammatory bowel diseases. All inflammatory bowel diseases cause chronic inflammation in the digestive system. Crohn’s disease most commonly occurs at the lower end of the small intestine (ileum) and the beginning of the large intestine (colon), but it can affect any part of the gastrointestinal tract (digestive system).

Symptoms

Specific symptoms of Crohn’s disease vary depending on where the disease is located in the intestinal tract (ileum, colon, stomach, duodenum, or jejunum). Common symptoms of Crohn’s disease include:

- Abdominal pain, usually in lower right side

- Diarrhea

- Weight loss

- Rectal bleeding

- Fever

- Nausea and vomiting

- Skin lesions

- Joint pain

Complications

Crohn’s disease can cause many different kinds of complications depending on its severity:

- Blockages or obstructions in the intestinal tract

- Fistulas and abscesses around the anus

- Malnutrition

- Increased risk for colorectal cancer

Treatment for Crohn's Disease

Crohn's disease is a chronic condition that cannot be cured, but appropriate treatment can help suppress the inflammatory response and manage symptoms. Treatment approaches include:

- Diet and nutrition management

- Drug treatment to resolve symptoms and prevent disease flare-ups

- Surgery is an option if medications and diet and lifestyle changes no longer help

Introduction

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a general term that includes two main disorders:

- Ulcerative colitis (UC)

- Crohn's disease (CD)

These two diseases are related, but they are considered separate disorders with somewhat different treatment options. The basic distinctions between UC and CD are location and severity. However, some patients with early-stage IBD have features and symptoms of both disorders. (This is called indeterminate colitis.)

Crohn's Disease. Crohn's disease is an inflammation that extends into the deeper layers of the intestinal wall. It is found most often in the area bridging the small and large intestines, specifically in the ileum and the cecum, sometimes referred to as the ileocecal region.

Less often, Crohn's disease develops in other parts of the gastrointestinal tract, including the anus, stomach, esophagus, and even the mouth. It may affect the entire colon or form a string of connected ulcers in one part of the colon. It may also develop as multiple scattered clusters of ulcers throughout the gastrointestinal tract, skipping healthy tissue in between.

Ulcerative Colitis. Ulcerative colitis is an inflammatory disease of the large intestine. Ulcers form in the inner lining, or mucosa, of the colon or rectum, often resulting in diarrhea, which may be accompanied by blood and pus. The inflammation is usually most severe in the sigmoid and rectum and typically diminishes higher in the colon. The disease develops uniformly and consistently until, in some people, the colon becomes rigid and foreshortened. [For more information, see In-Depth Report #69: Ulcerative colitis.]

The Gastrointestinal Tract

The gastrointestinal tract (the digestive system) is a tube that extends from the mouth to the anus. It is a complex organ system that first carries food from the mouth down the esophagus to the stomach and then through the small and large intestine to be excreted out through the rectum and anus.

Esophagus. The esophagus, commonly called the food pipe, is a narrow muscular tube, about 9 1/2 inches long, that begins below the tongue and ends at the stomach.

Stomach. In the stomach, acids and stomach motion break food down into particles small enough so that nutrients can be absorbed by the small intestine.

Small Intestine. The small intestine, despite its name, is the longest part of the gastrointestinal tract and is about 20 feet long. Food that passes from the stomach into the small intestine first passes through three parts:

- First it enters the duodenum

- Then the jejunum, and

- Finally the ileum

Most of the digestive process occurs in the small intestine.

Large Intestine. Undigested material, such as plant fiber, is passed next to the large intestine, or colon, mostly in liquid form. The colon is wider than the small intestine but only about 6 feet long. The colon absorbs excess water and salts into the blood. The remaining waste matter is converted to feces through bacterial action. The colon is a continuous structure, but it is characterized as having several components

Cecum and Appendix. The cecum is the first part of the colon and it gives rise to the appendix. These structures are located in the lower-right quadrant of the abdomen. The colon continues onward in several sections:

- The first section, the ascending colon, extends upward from the cecum on the right side of the abdomen.

- The second section, the transverse colon, crosses the upper abdomen to the left side.

- The third section extends downward on the left side of the abdomen toward the pelvis and is called the descending colon.

- The final section is the sigmoid colon.

Rectum and Anus. Feces are stored in the descending and sigmoid colon until they are passed through the rectum and anus. The rectum extends through the pelvis from the end of the sigmoid colon to the anus.

Causes

Doctors do not know exactly what causes inflammatory bowel disease. IBD appears to be due to an interaction of many complex factors including genetics, impaired immune system response, and environmental triggers. The result is an abnormal immune system reaction, which in turn causes an inflammatory response in the body’s intestinal regions. Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, like other IBDs, are considered autoimmune disorders.

The Inflammatory Response

An inflammatory response occurs when the body tries to protect itself from what it perceives as invasion by a foreign substance (antigen). Antigens may be viruses, bacteria, or other harmful substances.

In Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, the body mistakenly targets harmless substances (food, beneficial bacteria, or the intestinal tissue itself) as harmful. To fight infection, the body releases various chemicals and white blood cells, which in turn produce byproducts that cause chronic inflammation in the intestinal lining. Over time, the inflammation damages and permanently changes the intestinal lining.

Genetic Factors

Although the exact causes of inflammatory bowel disease are not known, genetic factors certainly play some role. Several identified genes and chromosome locations play a role in the development of ulcerative colitis, Crohn's disease, or both. Genetic factors appear to be more important in Crohn's disease, although there is evidence that both forms of inflammatory bowel disease have common genetic defects.

Environmental Factors

Inflammatory bowel disease is much more common in industrialized nations, urban areas, and northern geographical latitudes. It is not clear how or why these factors increase the risk for IBD. It could be that “Western” lifestyle factors (smoking, exercise, diets high in fat and sugar, stress) play a role. However, there is no strong evidence that diet or stress cause Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis, although they can aggravate the conditions.

Other possible environmental causes for Crohn’s are reduced exposure to sunlight and subsequent lower levels of Vitamin D, and reduced exposure during childhood to certain types of stomach bacteria and other microorganisms. So far, these theories have not been confirmed.

Risk Factors

About 1 million Americans suffer from inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), and about half of these patients have Crohn's disease. There are several risk factors for Crohn’s disease.

Age

Crohn’s disease can occur at any age, but it is most frequently diagnosed in people ages 15 - 35. About 10% of patients are children under age 18.

Gender

Men and women are equally at risk for developing Crohn’s disease.

Family History

Crohn’s disease tends to run in families, with 20 - 25% of patients having a close relative who also has the disease.

Race and Ethnicity

Crohn’s disease is more common among whites, although incidence rates have been increasing among African-Americans as well. It is less common among Latinos and Asians. Jewish people of Ashkenazi (Eastern European) descent are at 4 - 5 times higher risk than the general population.

Smoking

Smoking appears increases the risk of developing Crohn’s disease, and can worsen the course of the disease. (Conversely, smoking appears to decrease the risk of ulcerative colitis. However, because of the hazards of smoking, it should never be used to protect against ulcerative colitis.)

Appendectomy

Removal of the appendix (appendectomy) may be linked to an increased risk for developing Crohn’s disease, but a decreased risk for ulcerative colitis.

Symptoms

The two major inflammatory bowel diseases, ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease, share certain characteristics:

- Symptoms usually appear in young adults.

- Symptoms can develop gradually or have a sudden onset.

- Both are chronic. In either disease, symptoms may flare up (relapse) after symptom-free periods (remission) or symptoms may be continuous without treatment.

- Symptoms can be mild or very severe and disabling.

The specific symptoms of Crohn’s disease vary depending on where the disease is located in the intestinal tract (ileum, colon, stomach, duodenum, or jejunum). Common symptoms of Crohn’s disease include:

- Abdominal pain, usually in lower right side

- Diarrhea

- Weight loss

- Rectal bleeding

- Fever

- Nausea and vomiting

- Skin lesions

- Joint pain

Other Symptoms

Eyes. Inflammation in the eyes is sometimes an early sign of Crohn's disease. Retinal disease, including detachment, can occur but is rare. People with accompanying arthritic complications may be at higher risk for eye problems.

Joints. Inflammation causes arthritis and stiffness in the joints. The back is commonly affected. Patients with Crohn's disease are also at risk for clubbing (abnormal thickening and widening at the ends of fingers and toes).

Mouth Sores. Canker sores are common, and when they occur they persist. Mouth yeast infections are also common in people with Crohn's disease.

Skin Disorders. Patients with Crohn's disease may develop red knot-like swellings. Such swellings or other skin lesions, such as ulcers, may spread to sites far removed from the colon, (including the arms and legs). People with Crohn's disease have an increased risk for psoriasis.

Difference between Symptoms of Mild and Severe Crohn’s Disease

Mild Crohn's Disease. The fewer the number of bowel movements, the milder the disease. In mild disease, abdominal pain is absent or minimal. The patient has a sense of well-being that is normal or close to normal. There are few, if any, complications outside the intestinal tract. The doctor does not detect any mass when pressing the abdomen. The red blood cell count is normal or close to normal, and the patient is not underweight. There are no fistulas, abscesses, or other chronic changes.

Severe Crohn's Disease. In severe Crohn's disease, the patient has bowel movements frequent enough to need strong anti-diarrheal medication. Abdominal pain is severe and usually located in the lower right quadrant of the abdomen. (The location of the pain might not indicate the site of the actual problem, a phenomenon known as referred pain.) The red blood cell count is low. The patient has a poor sense of well-being and experiences complications that may include weight loss, joint pain, inflammation in the eyes, reddened or ulcerated skin, fistulas, abscesses, and fever. The surgical and medical treatments of Crohn's disease, as with ulcerative colitis, have complications of their own that can be severe.

Complications

Complications in the Intestine

Intestinal Blockage. Blockage or obstruction in the intestinal tract is a common complication of Crohn’s disease. Inflammation from Crohn's disease produces scar tissue known as strictures that can constrict the intestines, causing bowel obstruction with severe cramps and vomiting. Strictures usually occur in the small intestine but can also occur in the large intestine.

Fistulas and Abscesses. Inflammation around the anal area can cause fistulas and abscesses. Fistulas (abnormal channels between tissues) frequently develop from the deep ulcers that can form with Crohn's. If fistulas develop between the loops of the small and large intestines, they can interfere with absorption of nutrients. They often lead to pockets of infection, or abscesses, which may become life threatening if not treated.

Malabsorption and Malnutrition. Malabsorption is the inability of the intestines to absorb nutrients. In IBD, this occurs as a result of bleeding and diarrhea, as a side effect from some of the medications, or as a result of surgery. Malnutrition usually develops slowly and tends to become severe, with multiple nutritional deficiencies. It is very common in patients with Crohn's disease.

Toxic Megacolon. Toxic megacolon is a serious complication that can occur if inflammation spreads into the deeper layers of the colon. In such cases, the colon enlarges and becomes paralyzed. In severe cases, it may rupture, which is a life-threatening event that requires emergency surgery.

Colorectal Cancers. Inflammatory bowel disease increases the risk for colorectal cancer. The risk is highest for patients who have had the disease for at least 8 years or who have extensive areas of colon involvement. The more severe the disease, and the more it has spread throughout the colon, the higher the risk. Having a family history of colorectal cancer also increases risk. Patients with Crohn's disease also have an increased risk for small bowel cancer. (However, small bowel cancer is a very rare type of cancer.)

If you have an IBD, discuss with your doctor how often you should have a colonoscopy (screening test for colorectal cancer). Current guidelines recommend that patients receive an initial colonoscopy within 8 years after IBD is diagnosed, and have follow-up colonoscopies every 1 - 2 years. The colonoscopy should include biopsies to test for dysplasia (precancerous changes in cells). [For more information, see In-Depth Report #55: Colon and rectal cancers.]

Intestinal Infections. Inflammatory bowel disease can increase a patient's susceptibility to Clostridium difficile, a species of intestinal bacteria that causes severe diarrhea. It is usually acquired in a hospital. However, recent studies indicate that C. difficile is increasing among patients with inflammatory bowel disease and that many patients acquire this infection outside of the hospital setting. Patients with ulcerative colitis are at particularly high risk.

Complications outside the Intestine

Bones. Crohn’s disease, and the corticosteroid drugs used to treat it, can cause osteopenia (low bone density) and osteoporosis (bone loss).

Anemia. Internal blood loss from ulcers in the intestine is a particular problem in Crohn's disease because of the impaired ability to absorb vitamins and minerals necessary for blood production. This can lead to reduced red blood cell count and iron deficiency anemia.

Liver and Gallbladder Disorders. Patients have a higher than average risk for mild but not severe liver problems. They have double the normal risk for gallstones.

Mouth Sores. Canker sores are common, and when they occur they persist. Mouth yeast infections are also common in people with Crohn's disease.

Skin Disorders. Patients with Crohn’s disease are likely to develop red knot-like swellings. Such swellings or other skin lesions, such as ulcers, may spread to sites far removed from the colon, (including the arms and legs). People with Crohn's disease have an increased risk for psoriasis.

Thromboembolism (Blood Clots). People with inflammatory bowel disease are at higher risk for blood clots, especially deep venous thromboembolism where blood clots form in the legs. They are also at risk for pulmonary embolism, when a blood clot travels from the legs to the lungs.

Urinary Tract and Kidney Disorders. Urinary tract infections are common. Patients have an increased risk for kidney stones. Amyloidosis (deposits of a protein called amyloid in the kidney or other organs) is a rare but very serious kidney condition.

Delayed Growth and Development in Children. Up to half of children with Crohn’s disease have impaired physical growth and development, and nearly all are underweight.

Emotional Factors. The emotional consequences of Crohn’s disease are often difficult. Eating becomes associated with fear of abdominal pain before the end of the meal. Frequent attacks of diarrhea can cause such a strong sense of humiliation that social isolation and low self-esteem may result. Adolescents with IBD may have added problems that increase emotional distress, including weight gain from steroid treatments and delayed puberty.

Prognosis

The outlook for Crohn's disease varies widely. Crohn's disease can range from being benign (such as when limited Crohn's disease occurs only around the anus in older people) or it can be very severe. At the extreme end, some patients may experience only one episode and others suffer continuously. About 13 - 20% of patients have chronic Crohn’s disease.

Although recurrences tend to be normal, disease-free periods can last for years or decades in some patients. Although Crohn's disease cannot be cured even with surgery, treatments are now available that can offer significant help to most patients. Crohn's disease is rarely a direct cause of death, and most people can live a normal lifespan with this condition.

Diagnosis

There is no definitive diagnostic test for Crohn’s disease. A doctor will diagnose Crohn’s disease based on medical history and physical examination, and the results of laboratory, endoscopic (appearance and biopsy results), and imaging tests.

Laboratory Tests

- Blood tests are used for various purposes, including to determine the presence of anemia (low red blood cell count). An increased number of white blood cells or elevated levels of inflammatory markers such as C-reactive protein may indicate the presence of inflammation.

- A stool sample may be taken and examined for blood, infectious organisms, or both.

Endoscopy

Flexible Sigmoidoscopy and Colonoscopy. Flexible sigmoidoscopy and colonoscopy are procedures that involve snaking a fiber-optic tube called an endoscope through the rectum to view the lining of the colon. The doctor can also insert instruments through it to remove tissue samples.

- Sigmoidoscopy, which is used to examine only the rectum and left (sigmoid) colon, lasts about 10 minutes and is done without sedation. It may be mildly uncomfortable, but it is not painful.

- Colonoscopy allows a view of the entire colon and requires a sedative, but it is still a painless procedure performed on an outpatient basis. A colonoscopy can also help screen for colon cancer.

These procedures can help a doctor to distinguish between ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease, as well as other diseases.

Wireless Capsule Endoscopy. Wireless capsule endoscopy (WCE) is a newer imaging approach that is sometimes used for diagnosing Crohn's disease. With WCE, the patient swallows a capsule containing a tiny camera that records and transmits images as it passes through the gastrointestinal tract.

Imaging Procedures

Upper and Lower Gastrointestinal Barium X-Rays. An upper gastrointestinal barium x-ray may be used if Crohn's disease is suspected in the small intestine. Swallowed barium passes into the small intestine and shows up on an x-ray image, which may reveal inflammation, ulcers, and other abnormalities.

Other Imaging Tests. Transabdominal ultrasound, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT) scans may also be used to evaluate the patient’s condition.

Ruling Out Diseases Resembling Crohn's Disease

Ulcerative Colitis. Diarrhea associated with ulcerative colitis tends to be more severe than diarrhea caused by Crohn’s disease. Abdominal pain is more constant with Crohn’s disease than with ulcerative colitis. Fistulas and strictures are common with Crohn’s disease but very rare with ulcerative colitis. Endoscopy and imaging tests often reveal more extensive involvement through the entire gastrointestinal tract with Crohn’s disease than with ulcerative colitis.

Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), also known as spastic colon, functional bowel disease, and spastic colitis may cause some of the same symptoms as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). (However, it is NOT the same as inflammatory bowel disease.) Bloating, diarrhea, constipation, and abdominal cramps are all symptoms of IBS. Irritable bowel syndrome is not caused by inflammation, however, and no fever or bleeding occurs. Behavioral therapy may be helpful in treating IBS. (Psychological therapy does not improve inflammatory bowel disease.)

Celiac Sprue. Celiac sprue, or celiac disease, is an intolerance to gluten (found in wheat) that triggers inflammation in the small intestine and causes diarrhea, vitamin deficiencies, and stool abnormalities. It occurs in some people with inflammatory bowel disease and is usually first noticed in children.

Acute Appendicitis. Crohn's disease may cause tenderness in the right lower part of the abdomen, where the appendix is located, that resembles appendicitis.

Cancer. Colon or rectal cancers must always be ruled out when symptoms of IBD occur.

Intestinal Ischemia (Ischemic Colitis). Symptoms similar to IBD can be caused by blockage of blood flow in the intestine. This is more likely to occur in elderly people.

Treatment

Crohn’s disease cannot be cured, but appropriate treatment can help suppress the inflammatory response and manage symptoms. A treatment plan for Crohn’s disease includes:

- Diet and nutrition

- Medications

- Surgery

Diet and Nutrition

Malnutrition is very common in Crohn's disease. Patients with Crohn's disease have reduced appetite and weight loss. In addition, diarrhea and poor absorption of nutrients can deplete the body of fluid and necessary vitamins and minerals.

It is important to eat a well-balanced healthy diet and focus on getting enough calories, protein, and essential nutrients from a variety of food groups. These include protein sources such as meat, chicken, fish or soy; dairy products such as milk, yogurt, and cheese (if you are not lactose-intolerant); and fruits and vegetables.

Depending on your nutritional status, your doctor may recommend that you take a multivitamin or iron supplement. Although other types of dietary supplements, such as probiotics (“healthy bacteria” like lactobacilli) and omega-3 fatty acids, have been investigated for Crohn’s disease, there is no conclusive evidence that they are effective in controlling symptoms or preventing disease relapses.

Certain types of foods may worsen diarrhea and gas symptoms, especially during times of active disease. While people vary in their individual sensitivity to foods, general guidelines for dietary management during active disease include:

- Eat small amounts of food throughout the day.

- Stay hydrated by drinking lots of water (frequent consumption of small amounts throughout the day).

- Eat soft, bland foods and avoid spicy foods.

- Avoid high-fiber foods (bran, beans, nuts, seeds, and popcorn).

- Avoid fatty greasy or fried foods and sauces (butter, margarine, and heavy cream).

- Limit milk products if you are lactose intolerant (or consider taking a lactase supplement to improve tolerance). Otherwise, dairy products are a good source of protein and calcium.

- Avoid or limit alcohol and caffeine consumption.

In cases of severe malnutrition, particularly for children, patients may need enteral nutrition. Enteral nutrition uses a feeding tube that is inserted either through the nose and down through the throat or directly through the abdominal wall into the gastrointestinal tract. It is the preferred method for feeding patients with malnutrition who cannot tolerate eating by mouth. Unfortunately, it is not likely to help patients with malabsorption caused by extensive intestinal disease. Enteral nutrition can be effective for helping maintain remission.

Medications

The goal of drug therapy for Crohn’s disease is to:

- Resolve symptoms (induce remission)

- Prevent disease flare-ups (maintain remission). The main drugs used for maintenance are azathioprine, methotrexate, infliximab, and adalimumab.

Depending on the severity of the condition, different types of drugs are used. The main medications for Crohn’s disease include:

- Aminosalicylates (5-ASAs) are anti-inflammatory drugs, which are usually used to treat mild-to-moderate disease. The standard aminosalicylate used for Crohn’s disease is sulfasalazine (Azulfidine, generic).

- Corticosteroids are used to treat moderate-to-severe disease. Common corticosteroids include prednisone (Deltasone, generic) and methylprednisone (Medrol, generic). Budesonide (Entocort) is a newer type of steroid. Because corticosteroids can have severe side effects, they are usually used short-term to induce remission, but NOT for maintenance therapy.

- Immunosuppressives, also called immunomodulators or immune modifiers, block actions in the immune system that are involved with the inflammatory response. Standard immunosuppressives include azathioprine (Imuran, Azasan, generic), 6-mercaptopurine (6-MP, Purinethol, generic), and methotrexate (Rheumatrex, generic). These drugs are used for long-term maintenance therapy and to help decrease corticosteroid dosages.

- Biologic drugs are generally used to treat moderate-to-severe disease. They include infliximab (Remicade), adalimumab (Humira), certolizumab (Cimzia), and natalizumab (Tysabri). Infliximab, adalimumab, and certolizumab target the inflammatory immune factor known as tumor necrosis factor (TNF). They also target the immune system.

Other types of drugs may also be used to treat specific conditions and symptoms. Antibiotics, usually ciprofloxacin or metronidazole, may be used to treat fistulas. Anti-diarrheal medications such as loperamide (Imodium) may be given to help control diarrhea.

Drug therapy for Crohn’s disease is considered successful if it can push the disease into remission (and keep it there) without causing significant side effects. The patient's condition is generally considered in remission when the intestinal lining has healed and symptoms such as diarrhea, abdominal cramps, and tenesmus (painful defecation) are normal or close to normal.

Surgery

Most patients with Crohn’s disease eventually need some type of surgery. However, surgery cannot cure Crohn's disease. Problems with fistulas and abscesses may occur after surgeries. New disease usually recurs in other areas of the intestine. Surgery may be helpful for relieving symptoms and to correct intestinal blockage, bowel perforation, fistulas, or bleeding.

Basic types of surgery used for Crohn’s disease include:

- Strictureplasty is used to help open up strictures, narrowed areas of intestine.

- Resection is used to remove damaged sections of the bowel. The surgeon reattaches the cut ends of the intestine in a procedure called an anastomosis. Repeat resections may be needed if the disease recurs at a different site near the anastomosis.

- Colectomy (removal of the colon) or proctocolectomy (removal of the colon and rectum) may be performed in cases of severe Crohn’s disease. After a proctocolectomy is completed, the surgeon performs an ileostomy in which the surgeon connects the end of the small intestine (ileum) to a small opening in the abdomen (called a stoma). Patients who have had a proctolectomy and ileostomy need to wear a pouch over the stoma to collect waste. Patients who have had a colectomy can continue to pass stool naturally.

- Other surgical procedures include repairing fistulas that have not been helped by medication, and draining abscesses.

Medications

Aminosalicylates (5-ASAs)

Aminosalicylates contain the compound 5-aminosalicylic acid, or 5-ASA, which helps reduce inflammation. These drugs are used to prevent relapses and maintain remission in mild-to-moderate Crohn’s disease.

The standard aminosalicylate drug is sulfasalazine (Azulfidine, generic). This drug combines the 5-ASA drug mesalamine with sulfapyridine, a sulfa antibiotic. While sulfasalazine is inexpensive and effective, the sulfa component of the drug can cause unpleasant side effects, including headache, nausea, and rash.

Patients who cannot tolerate sulfasalazine, or who are allergic to sulfa drugs, have other options for aminosalicylate drugs, including mesalamine (Asacol, Pentasa, generic), olsalazine (Dipentum), and balsalazide (Colazal, generic). These drugs, like sulfasalazine, are available as pills. Mesalamine is also available in enema (Rowasa, generic) and suppository (Canasa, generic) forms.

Mesalamine can cause kidney problems and should be used with caution by patients with kidney disease. Common side effects of aminosalicylate drugs include:

- Abdominal pain and cramps (mesalamine, balsalazide)

- Diarrhea (mesalamine, olsalazine)

- Gas (mesalamine)

- Nausea (mesalamine)

- Hair loss (mesalamine)

- Headache (mesalamine, balsalazide)

- Dizziness (mesalamine)

All mesalamine preparations, including sulfasalazine, appear to be safe for children, and for women who are pregnant or nursing.

Corticosteroids

Corticosteroids (commonly called steroids) are powerful anti-inflammatory drugs used for treating Crohn's disease in adults. Because of their severe side effects, steroids should be reserved for those with moderate-to-severe disease or those who relapse after other therapies. Steroids appear to be safe for pregnant women and can be used if necessary during pregnancy. Long-term usage is avoided if possible because of side effects.

Corticosteroids are frequently combined with other drugs, such as 5-ASA drugs, to produce more rapid symptom relief and to allow quicker withdrawal, although such combinations do not improve remission time.

In general, corticosteroids are recommended only for short-term use for achieving remission in active Crohn's disease. The lowest effective dose should be used for the shortest amount of time. Long-term treatments cause significant side effects, and alternative drugs exist. Corticosteroids do not prevent flare-ups and are rarely used for maintenance treatment.

Patients who are malnourished are less likely to respond to steroids, and those who had an initial inadequate response to steroids are also less likely to do well with repeat therapy. Some patients who have had Crohn's disease for a long time may have partial or complete resistance to corticosteroids.

Corticosteroid Types. Prednisone (Deltasone, generic), methylprednisolone (Medrol, generic), and hydrocortisone (Cortef, generic) are the most common corticosteroids. Newer steroids, such as budesonide (Entocort), affect only local areas in the intestine and do not circulate throughout the body, which may help reduce widespread side effects.

Administering Corticosteroids. Most corticosteroids can be taken as a pill. For patients who cannot take oral forms, methylprednisolone and hydrocortisone may also be given intravenously, or rectally as a suppository, enema, or foam. The severity or location of the condition often determines the form.

Side Effects of Corticosteroids. Standard steroids can have distressing and sometimes serious long-term side effects, including:

- Susceptibility to infection

- Weight gain (particularly increased fatty tissue on the face and upper trunk and back)

- Acne

- Excess hair growth

- High blood pressure (hypertension)

- Weakened bones (osteoporosis)

- Cataracts and glaucoma

- Diabetes

- Muscle wasting

- Menstrual irregularities

- Upper gastrointestinal ulcers

- Personality change, including irritability, insomnia, depression, and psychosis

Withdrawing from Corticosteroids. Once the intestinal inflammation has subsided, steroids must be withdrawn very gradually. Withdrawal symptoms, including fever, malaise, and joint pain, may occur if the dosage is lowered too rapidly. If this happens, the dosage is increased slightly and maintained until symptoms are gone. More gradual withdrawal is then resumed.

Immunosuppressive Drugs

For very active inflammatory bowel disease that does not respond to standard treatments, immunosuppressant drugs are used for long-term therapy. Such drugs suppress or limit actions of the immune system and therefore the inflammatory response that causes Crohn's disease. Immunosuppressants may help maintain remission in Crohn's disease and heal fistulas and intestinal ulcers caused by this disease. These drugs are sometimes combined with a corticosteroid drug for treating active disease flares.

Azathioprine (Imuran, Azasan, generic) and mercaptopurine (6-MP, Purinethol, generic) are the standard oral immunosuppressant drugs. However, it can take 3 - 6 months for these drugs to have an effect. To speed up the response, they are sometimes prescribed along with a corticosteroid drug. Lower steroid doses are then needed, resulting in fewer side effects. Corticosteroids may also be withdrawn more quickly. For this reason, immunosuppressants are sometimes referred to as steroid-sparing drugs.

Other pill forms of immunosuppressants include cyclosporine A (Sandimmune, Neoral, generic) and tracrolimus (Prograf, generic). These drugs are faster-acting than azathiopine and mercaptopurine. Cyclosporine A generally takes 1 - 2 weeks to take effect. For patients who have Crohn’s disease accompanied by fistulas, Cyclosporine A may be given intravenously. For patients whose condition affects the mouth or area around the anus, tracrolimus is available as a topical ointment.

Methotrexate [(MTX), Rheumatrex, generic] is another fast-acting type of immunosuppressant. It is given weekly and may be an option for patients with severe Crohn’s disease who have not been helped by other immunosuppressant drugs. However, methotrexate can cause miscarriages and birth defects (as well as liver damage). Because of these complications, both men and women who take methotrexate should use birth control.

General side effects of immunosuppressants may include nausea, vomiting, and liver or pancreatic inflammation. Patients should receive frequent blood tests to monitor bone marrow, liver, and kidneys. Patients who take cyclosporine A or tacrolimus need to have their blood pressure and kidney function checked regularly. Children and young adults who take azathioprine or mercaptopurine should be monitored for signs of cancer as these drugs have been associated with increased risk of an aggressive form of T-cell lymphoma. Immunosuppressants are usually not recommended for women who are pregnant or breast-feeding.

Biologic Drugs

Biologic response modifiers are genetically engineered drugs that target specific proteins involved with the body's inflammatory response.

The American Gastroenterological Association recommends that, in general, biologic drugs should not be used as first-line treatment for most patients with Crohn's disease. However, some patients with moderate-to-severe disease -- especially those who have not responded to corticosteroids or who suffer from fistulas -- may benefit from initial treatment with infliximab or other biologic drugs. In all cases, the benefits of biologic drugs need to be weighed against their potential risks, which can include increased risk for infections, lymphoma, and drug-related side effects.

Tumor necrosis factor (TNF) blockers, which include infliximab, adalimumab, and certolizumab, can increase the risk for cancer, particularly lymphomas, in children and adolescents. They can also increase the risk for leukemia in patients of all ages.

Some patients who take anti-TNF drugs develop psoriasis. Fungal infections and tuberculosis are also serious concerns for patients who take anti-TNF drugs. Doctors should carefully monitor patients on anti-TNF therapy for any signs of infection. Symptoms of fungal infections include fever, malaise, weight loss, sweating, cough, and shortness of breath.

Infliximab. Infliximab (Remicade) is an anti-TNF drug that was the first biologic drug approved for treating adults and children with Crohn's disease.

Infliximab is used to help control symptoms and to induce and keep the disease in remission. Infliximab is also used to reduce the number of fistulas and maintain fistula closure. Common side effects of infliximab include respiratory infections (sinus infections and sore throat), headache, rash, cough, and stomach pain. Like all anti-TNF drugs, inflixmab can potentially cause serious severe side effects, including increased susceptibility to viral, fungal, and bacterial infections (including tuberculosis). Other severe side effects may include lymphoma (a type of cancer), heart failure, liver failure aplastic anemia, nervous system disorders, and allergic reactions.

Adalimumab. Adalimumab (Humira) is a biologic drug used for inducing and achieving remission in adult patients with moderate-to-severe Crohn's disease. Like infliximab, adalimumab blocks TNF. Also approved for treating symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis, adalimumab requires injections to initiate treatment, followed by a maintenance shot every other week.

In addition to pain at the injection site, common side effects of adalumimab include upper respiratory infections, headache, rash, and nausea. Adalimumab’s potential severe side effects are similar to those of infliximab. In addition, adalimumab may reactivate hepatitis B in patients who carry the virus in their blood.

Certolizumab. Certolizumab (Cimzia) is another anti-TNF drug given by injection. Patients receive an injection every 2 weeks for the first 3 weeks. Once patients show signs of improvement, they receive an injection once a month. Certolizumab’s side effects are similar to those of adalimumab and infliximab.

Natalizumab. Natalizumab (Tysabri) is also a biologic drug, but it does not target TNF. Instead, natalizumab affects white blood cells involved in the inflammatory response. Natalizumab is given by intravenous infusion once a month in a doctor’s office or hospital infusion clinic.

Because natalizumab carries some serious potential risks, patients who take this medication must enroll in a special program that helps the FDA monitor side effects of the drug. The most serious side effect is increased risk for a rare neurological condition called progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML), which can lead to death or severe disability. The risk for PML increases when patients have more than 24 infusions of natalizumab (2 years of treatment).

Other serious side effects of natalizumab include allergic reactions, and increased susceptibility to infections including serious herpes infections. In general, natalizumab should not be used by patients who are currently taking immunosuppressant drugs.

Natalizumab may cause liver injury within a week of starting the drug. Other less serious side effects may include headache, fatigue, urinary tract infections, joint and limb pain, rash, and infusion reactions.

Other Medications

Antibiotics. Antibiotics may be used as a first-line treatment for fistulas, bacterial overgrowth, abscesses, and any infections around the anus and genital areas. Standard antibiotics include ciprofloxacin (Cipro, generic) and metronidazole (Flagyl, generic). Ciprofloxacin is the antibiotic of choice.

Over time, metronidazole can cause peripheral neuropathy, a nerve disorder that can cause numbness and tingling in the hands and feet. Other side effects associated with metronidazole include nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, loss of appetite, dizziness, and headaches.

Although ciprofloxacin causes fewer side effects than metrondizaole, it can interact with antacids (Rolaids, Tums) and vitamin and mineral supplements that contain calcium, iron, or zinc. Do not take antacids or vitamin supplements at the same time as the ciprofloxacin dose.

Anti-Diarrheal Drugs. Mild-to-moderate diarrhea may be reduced by daily use of psyllium (Metamucil, generic). Standard anti-diarrheal medications include loperamide (Imodium, generic) or a combination of atropine and diphenoxylate (Lomotil, generic). In some cases, codeine may be prescribed.

Surgery

Strictureplasty

The chronic inflammation of Crohn’s disease can eventually cause scarring, which leads to narrowing in certain segments of the intestine. These narrowed areas are called strictures. If strictures do not respond to medication, a surgical procedure called strictureplasty may be used to open the blockage and widen the narrow passages.

Strictureplasty is usually performed for repairing strictures in the jejunum or ileum sections of the small intestine. It involves cutting open the strictured segment and stitching the tissue crosswise. This helps remove the area obstructing the bowel and enlarges the width of the passageway, without removing any parts of the intestine.

Resection and Anastomis

When Crohn’s disease penetrates or severely inflames the bowel or colon, patients may require surgical resection. Resection is also performed for patients who have signs of small or large bowel perforation. (Perforation is when a hole in the bowel lets waste contents flow into the abdominal cavity.)

Resection involves removing the diseased section of the bowel and then reattaching the healthy ends of the intestine in a procedure called an anastomis. Resection can be performed either through open surgery involving a wide incision through the abdomen, or through less-invasive laparoscopy.

Disease Recurrence after Resection. About half of patients experience a recurrence of active Crohn’s disease within 5 years of having resection and require a second surgery. The disease usually recurs near the site of the anastomis. Medications such as aminosalicylates and immunosuppressive drugs are given to help prevent or delay recurrence.

Colectomy, Proctocolectomy, and Ileostomy

If Crohn’s disease becomes extremely severe, and other treatments do not help, the patient may need to have their entire colon removed. If the rectum is also affected, it will also need to be removed.

- Colectomy is surgical removal of the entire colon.

- Proctocolectomy is surgical removal of the entire colon and rectum.

Patients who have colectomy still retain their rectums and are able to pass stool naturally. Because proctocolectomy involves removing the rectum, the surgeon must perform another procedure, called ileostomy, after proctocolectomy to create an opening to allow waste to pass

Proctocolectomy with ileostomy involves the following:

- To perform proctocolectomy, the surgeon removes the entire colon, including the lower part of the rectum and the sphincter muscles that control bowel movements.

- To perform ileostomy, the surgeon makes a small opening in the lower right corner of the abdomen called a stoma. The surgeon then connects cut ends of the small intestine to this opening. An ostomy bag is placed over the opening and accumulates waste matter. It requires emptying several times a day.

Other Surgeries

Surgery may also be performed to treat fistulas or drain abscesses that have not been helped by medication, to control excessive bleeding, and to remove intestinal obstructions.

Resources

- www.ccfa.org -- Crohn's & Colitis Foundation of America

- www.gastro.org -- American Gastroenterological Association

- www.acg.gi.org -- American College of Gastroenterology

- www2.niddk.nih.gov -- National Digestive Diseases Information Clearinghouse

References

Abraham C, Cho JH. Inflammatory bowel disease. N Engl J Med. 2009 Nov 19;361(21):2066-78.

Akobeng AK. Crohn's disease: current treatment options. Arch Dis Child. 2008;93(9): 787-92.

Akobeng AK and Thomas AG. Enteral nutrition for maintenance of remission in Crohn's disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(3): CD005984.

Ananthakrishnan AN, Khalili H, Higuchi LM, Bao Y, Korzenik JR, Giovannucci EL, et al. Higher predicted vitamin D status is associated with reduced risk of Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 2012 Mar;142(3):482-9. Epub 2011 Dec 9.

Baumgart DC and Sandborn WJ. Inflammatory bowel disease: clinical aspects and established and evolving therapies. Lancet. 2007;369(9573): 1641-57.

Bernstein CN, Fried M, Krabshuis JH, Cohen H, Eliakim R, Fedail S, et al. World Gastroenterology Organization Practice Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of IBD in 2010. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2010 Jan;16(1):112-24.

Burger D, Travis S. Conventional medical management of inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2011 May;140(6):1827-1837.e2.

Butterworth AD, Thomas AG, Akobeng AK. Probiotics for induction of remission in Crohn's disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008 Jul 16;(3):CD006634.

Clark M, Colombel JF, Feagan BC, Fedorak RN, Hanauer SB, Kamm MA, et al. American gastroenterological association consensus development conference on the use of biologics in the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease, June 21-23,2006. Gastroenterology. 2007 Jul;133(1):312-39.

Cummings JR, Keshav S and Travis SP. Medical management of Crohn's disease. BMJ. 2008;336(7652):1062-6.

Doherty G, Bennett G, Patil S, Cheifetz A, Moss AC. Interventions for prevention of post-operative recurrence of Crohn's disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009 Oct 7;(4):CD006873.

Farraye FA, Odze RD, Eaden J, Itzkowitz SH, McCabe RP, Dassopoulos T, et al. AGA medical position statement on the diagnosis and management of colorectal neoplasia in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2010 Feb;138(2):738-45.

Ford AC, Achkar JP, Khan KJ, Kane SV, Talley NJ, Marshall JK, et al. Efficacy of 5-aminosalicylates in ulcerative colitis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011 Apr;106(4):601-16. Epub 2011 Mar 15.

Ford AC, Bernstein CN, Khan KJ, Abreu MT, Marshall JK, Talley NJ, et al. Glucocorticosteroid therapy in inflammatory bowel disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011 Apr;106(4):590-9; quiz 600. Epub 2011 Mar 15.

Ford AC, Sandborn WJ, Khan KJ, Hanauer SB, Talley NJ, Moayyedi P. Efficacy of biological therapies in inflammatory bowel disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011 Apr;106(4):644-59, quiz 660. Epub 2011 Mar 15.

Khan KJ, Dubinsky MC, Ford AC, Ullman TA, Talley NJ, Moayyedi P. Efficacy of immunosuppressive therapy for inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011 Apr;106(4):630-42. Epub 2011 Mar 15.

Khan KJ, Ullman TA, Ford AC, Abreu MT, Abadir A, Marshall JK, et al. Antibiotic therapy in inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011 Apr;106(4):661-73. Epub 2011 Mar 15.

Lichtenstein GR, Hanauer SB, Sandborn WJ; Practice Parameters Committee of American College of Gastroenterology. Management of Crohn's disease in adults. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009 Feb;104(2):465-83. Epub 2009 Jan 6.

Mahid SS, Minor KS, Soto RE, Hornung CA and Galandiuk S. Smoking and inflammatory bowel disease: a meta-analysis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2006;81(11):1462-71.

Molodecky NA, Soon IS, Rabi DM, Ghali WA, Ferris M, Chernoff G, et al. Increasing incidence and prevalence of the inflammatory bowel diseases with time, based on systematic review. Gastroenterology. 2012 Jan;142(1):46-54.e42. Epub 2011 Oct 14.

Mowat C, Cole A, Windsor A, Ahmad T, Arnott I, Driscoll R, et al. Guidelines for the management of inflammatory bowel disease in adults. Gut. 2011 May;60(5):571-607.

Rahimi R, Nikfar S, Rahimi F, Elahi B, Derakhshani S, Vafaie M, et al. A meta-analysis on the efficacy of probiotics for maintenance of remission and prevention of clinical and endoscopic relapse in Crohn's disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2008;53(9):2524-31.

Rutgeerts P, Vermeire S, Van Assche G. Biological therapies for inflammatory bowel diseases. Gastroenterology. 2009 Apr;136(4):1182-97. Epub 2009 Feb 26.

Strong SA, Koltun WA, Hyman NH, Buie WD; Standards Practice Task Force of The American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons. Practice parameters for the surgical management of Crohn's disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50(11):1735-46.

Timmer A, Preiss JC, Motschall E, Rücker G, Jantschek G, Moser G. Psychological interventions for treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011 Feb 16;(2):CD006913.

Wilkins T, Jarvis K, Patel J. Diagnosis and management of Crohn's disease. Am Fam Physician. 2011 Dec 15;84(12):1365-75.

Yamamoto T, Fazio VW, Tekkis PP. Safety and efficacy of strictureplasty for Crohn's disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50(11):1968-86.

Zachos M, Tondeur M and Griffiths AM. Enteral nutritional therapy for induction of remission in Crohn's disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(1):CD000542.

|

Review Date:

12/21/2012 Reviewed By: Harvey Simon, MD, Editor-in-Chief, Associate Professor of Medicine, Harvard Medical School; Physician, Massachusetts General Hospital. Also reviewed by David Zieve, MD, MHA, Medical Director, A.D.A.M. Health Solutions, Ebix, Inc. |